Lewis Mangaba – Wilderness Guide of Hwange

Near the end of last year, I spent some quality time with Wilderness Safari’s guide Lewis Mangaba in Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe. He is based at Linkwasha Camp in the south-east of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, where wildlife sightings are among the most impressive in Southern Africa.

I connected straight away with his softly-spoken and gentle nature. But his knowledge, experience and people skills as a guide deserves to be shouted from the rooftops.

For more than 20 years Lewis has been guiding visitors to some of the wildest places on the continent. And Hwange is certainly one of these. Predictably, Lewis has seen some amazing things.

“Once, at Madison Pan near Little Makalolo Camp, 15 lions killed a buffalo. Then 22 hyenas pitched up. We watched the lions and hyenas fighting for several hours.”

“Also at Little Makalolo, four hyenas chased a buffalo into camp and killed it within metres of the guests in camp.”

“At Davison’s Camp, three wild dogs chased a kudu into the dining room while guests were having breakfast. The kudu hid inside for a while, then ran out and the wild dogs killed it and ate the intestines and organs in front of the guests!”

Part of a super pride of lions, which were watching us within metres of Linkwasha Camp

There are no fences around any of the Wilderness Safaris’ camps in Hwange, and lions have right of way! Careful where you walk after sunset…

Although Lewis is a Shona, he grew up in the Tonga area of Kariba, near the dam wall that holds back the waters of Kariba Dam. In 1914, the English colonial government moved his grandfather’s family from the predominantly Shona-speaking highlands of Mutare in the east of Zimbabwe to the north of the country, near the Matusadona wildlife area on the Zambezi River valley.

“We lost our land, our homes and could only keep ten cattle. When the dam wall was built in 1956, we were forced to move again.”

Lewis is one of fives sons. His grandfather Lucas Mola was a local chief in the Omay area on the Zambezi River. As a young boy he was a cattle herder, and when hunters came to the Matusadona, Lewis would track elephants, which kept raiding the village crops.

“The hunters didn’t know the area, so I would find the elephants for them.”

In those days, Lewis says, the money from the elephant hunts would pay for the construction of new schools.

In 1992, as a 17-year-old, Lewis started working as white-water rafting guide on the infamously huge rapids below Victoria Falls.

“One year of that was enough for me,” Lewis chuckles, his smile broadening across his face. “Most of the river guides were older Ndebele guys. There’s a traditional rivalry between them and the Shona. So, because I was a new river guide and a Shona, they always made me carry the heavy rafts out of the steep gorge!”

In 1997, he started working as an apprentice under respected guide Benson Siyawareva in Hwange. In 2011, Lewis qualified as a Zimbabwean professional wildlife guide.

The four-year Zimbabwean qualification is considered the most stringent – and best in Africa. Qualifying guides have to spend a minimum of two years training as an apprentice under a fully licensed guide. To cap it off, the learner guide is submitted to a weeklong practical examination in the field by a panel of assessors, themselves experienced professional guides. The weeklong examination includes tracking, bush survival and close encounters with charging lions, elephants and buffalo.

Lewis has diverse experience. His formative years were spent working throughout Zimbabwe’s legendary wild areas, guiding visitors on walking and canoeing safaris through areas with dangerous wildlife.

For seven years he worked in the immense arid lands of Sossuvlei and Etosha in Namibia, and for 4 years in the savannahs and woodlands of Serengeti, Ngorongoro and Ruaha in East Africa.

In 2014 he was voted by readers of the UK’s Wanderlust Magazine as “World Guide of the Year”. He is regularly contracted by safari companies to train other guides around Africa. From 2011 to 2015, Lewis was the guiding instructor for the highly-respected Asilia Africa group of lodges. But he missed his family, his wife and children too much, so he came back to Hwange, which “will always be my home,” he says. “It’s still my favourite place in the world.”

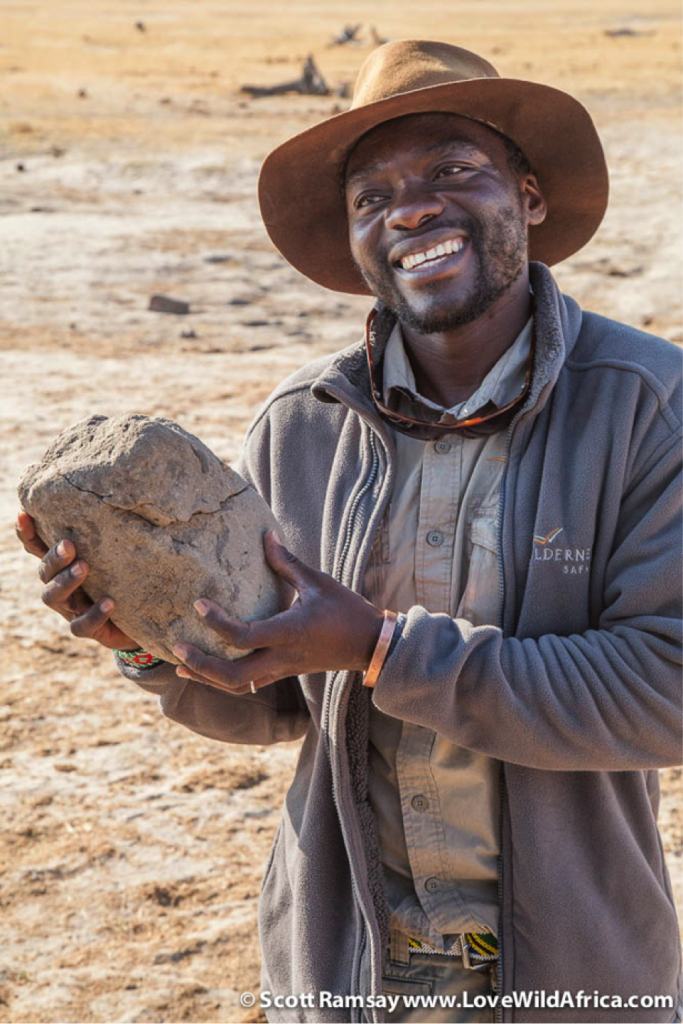

Lewis explaining how elephants will chew and eat the clay in the soil, to aid digestion and to add much-needed minerals to their diet.

Lewis doing what he does best… interpreting wild animal behaviour, and ensuring fantastic experiences for his guests!

According to Lewis, Hwange is the best place in Africa to see elephants, after Chobe National Park. You can see why!

While the north and west of Hwange comprises mostly thick mopane woodland, the open plains and grasslands around Linkwasha make for fantastic wildlife viewing. Hwange National Park lies on the eastern edge of the Kalahari semi-desert biome, so there’s no perennial surface water. Wilderness Safaris and other lodges pump water into the pans, which ensures high densities of wildlife, especially during the dry winter months of June to November.

“After Chobe National Park in Botswana, Hwange is probably the best place in Africa to see elephants. Selous used to be the best, but it’s been hit so hard by poachers. In Hwange, there are about 40 000 elephants, or about 3 per square kilometre, one of the highest densities in Africa. I know Hwange so well, and have worked here for so long. It’s a big, large area, with little population pressure on its perimeter.”

“The lion prides are big, up to 30 strong, and are particularly wild. You have to be very careful about walking in Hwange. Just the other day, another guide called me on his radio for help. He had taken guests out walking, and lions had surrounded them. We had to drive in there with a 4×4 to go rescue them.”

“The buffalo herds are also impressive, and sometimes can number more than 1 000 individuals in a herd. Then there’s good numbers of interesting species like sable, roan and eland antelope. And in summer time, Ngamo Plains is one of the best places in Africa to see raptors.”

To Lewis, wildlife is something more than something for visitors to look at and admire. Yes, he agrees, wildlife is critical for African economies, because it gives value to land, which would otherwise be run over by goats and cattle. And it provides jobs to people. “Just look at my life,” Lewis says. “Wildlife tourism has given me a job – and a meaning.”

But for him, the wild animals of Zimbabwe have more than just economic value. Wild animals give people an identity, he tells me.

“Many Zimbabweans are called by animal names. We identify with animals. And each animal has it’s own poetry. The problem with Zimbabweans is that some of us have forgotten who we are and where we come from. We are confused. Wild animals help us remember our roots.”

Sundowners with guests at a pan near Linkwasha as the elephants come to drink

Watching the full moon rise over Hwange, as elephant herds drink from the pan must rate as one of the finest experiences in Africa

One morning, Lewis and I spotted this caracal! It was the first wild caracal I had ever seen… it was long overdue – and very lucky to see one.

Davison’s Camp Manager Kimi White watches some elephants drink from the camp’s pan.

My room at Linkwasha… I am used to roughing it, so this made a nice change.

Written and Photographed by Scott Ramsay

Scott Ramsay of Love Wild Africa is a photojournalist telling the stories of protected areas, national parks and nature reserves in Africa. Ramsay is an ambassador for Cape Union Mart, K-Way and Ford Ranger. Supported by Escape Gear, EeziAwn, National Luna, Safari Centre Cape Town, Goodyear, Outdoor Photo and Hetzner.